Alamy

AlamyIt looked like an ordinary murder.

One hundred years ago today, on January 12, 1925, a group of men attacked a driving couple in an upscale suburb of colonial Bombay (now Mumbai), shooting the man to death and slashing the woman’s face. .

But the story as it unfolded captured global attention, and its complexities posed a dilemma for the British rulers of the day, ultimately forcing the Indian king to abdicate.

Newspapers and magazines described the murder as “perhaps the most sensational crime to occur in British India” and became “the talk of the town” during the investigation and subsequent trial.

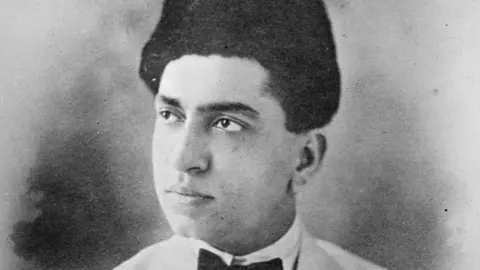

The victim, Abdul Kadir Bawla, 25, was an influential textile businessman and the city’s youngest municipal official. His female companion, 22-year-old Mumtaz Begum, a prostitute who escaped from the palace harem, had been living with Baula for the past few months.

On the night of the murder, Baula and Mumtaz Begum were driving with three others in the Malabar Hills, a wealthy area on the coast of the Arabian Sea. Cars were rare in India at that time and only the rich owned them.

Suddenly, another car overtook them. Before they could react, it collided with them, forcing them to stop, according to intelligence and newspaper reports.

Mumtaz Begum later told the Bombay High Court that the attacker cursed Baula and shouted “get this lady out”.

They then shot Baura, who died hours later.

A group of British soldiers on their way back from playing golf accidentally took the wrong route and rushed to the scene after hearing gunshots.

They managed to capture one of the gangsters, but one of the attackers opened fire on them, causing a gunshot wound to a police officer.

Alamy

AlamyThe remaining attackers twice tried to snatch injured Mumtaz Begum from British officers as they tried to take her to hospital before escaping.

Newspapers suggested that the attackers’ target was likely to kidnap Mumtaz Begum, as Bawla had met her while performing in Mumbai a few months ago, had been living together since then, and had earlier received multiple threats for sheltering her.

The Illustrated Weekly of India promised readers exclusive photos of Mumtaz Begum, while the police planned to issue daily bulletins to the media, Marathi newspaper Navakal reported.

Even Bollywood found the case compelling enough to adapt it into a silent murder thriller within months.

“The case goes beyond the usual murder mystery as it involves a wealthy young tycoon, a scorned king and a beautiful woman,” says “Murder at Baula: Love, Desire, and Love in Colonial India” said Dhawar Kulkarni, author of Crime.

As the media speculated, the attackers’ tracks led investigators to the influential princely state of Indore, a British ally. Mumtaz Begum was a Muslim who lived in the harem of the Hindu king Maharaja Tukoji Rao Holkar III.

Mumtaz Begum is famous for her beauty. KL Gauba wrote in his 1945 book The Famous Trial of Love and Murder: “It is said that Mumtaz was unrivaled in her own class.”

But Kulkarni said the maharaja’s (king) attempts to control her – preventing her from seeing her family alone and constantly monitoring her – soured their relationship.

“I was under surveillance. I was allowed to meet visitors and my relatives, but I was always accompanied by someone,” Mumtaz Begum testified in court.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Indore, she gave birth to a baby girl, but died soon after.

“I was not willing to stay in Indore after my child was born. I was not willing because the nurse killed the baby girl at birth,” Mumtaz Begum told the court.

Within months, she fled to the northern Indian city of Amritsar, where her mother was born, but trouble ensued.

She was also being watched there. Mumtaz Begum’s stepfather told the court that the Maharaja cried and begged her to return. But she refused and moved to Mumbai, where the surveillance continued.

The trial confirmed what the media had suspected after the murder: the Maharaja’s representatives had indeed threatened Baura with dire consequences if he continued to harbor Mumtaz Begum, but he ignored these warnings.

Acting on a tip from Shafi Ahmed, the only attacker captured at the scene, Mumbai police arrested seven men from Indore.

The investigation revealed connections to the Maharaja that were hard to ignore. Most of the arrested men were employed by the Maharaja of Indore, had applied for leave around the same time and were in Mumbai at the time of the incident.

The murder put the British government in a difficult position. Although the incident took place in Mumbai, investigations clearly revealed that the conspiracy was hatched in Indore, which had close ties with the British.

The New Statesman called it the British government’s “most embarrassing episode” and wrote that had it been a small state there would have been “no particular reason for anxiety”.

“But Indore has always been a powerful vassal of British India,” it said.

The British government initially tried to remain publicly silent about the murder’s connection to Indore. But communications between the Bombay government and the British Indian government show that privately it discussed the issue with great vigilance.

Mumbai Police Commissioner Patrick Kelly told the British government that all evidence “so far points to a conspiracy hatched by, or at the instigation of, Indore to abduct Mumtaj through hired desperadoes”.

The government is under pressure from all sides. The wealthy Memons community of Baura, a Muslim community with origins in modern-day Gujarat, raised the issue with the government. His fellow city officials expressed condolences at his death and said “there must have been something else going on behind the scenes.”

Indian MPs demanded answers from the House of Lords, the British Raj’s legislative body, and the British House of Commons even discussed the case.

Alamy

AlamyFormer police officer Rohidas Narayan Dusar wrote in his book about the murder that investigators faced pressure to move slowly, but then-Police Chief Kelly threatened to resign.

When the case reached the Bombay High Court, both the defense and prosecution hired top lawyers.

One of them was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who later became the founding father of Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947. Jinnah defended one of the accused, Anandrao Gangaram Phanse, a senior general in the Indore army. Jinnah managed to save his client from execution.

The court sentenced three men to death and three to life imprisonment, but did not hold the Maharaja accountable.

However, Judge LC Crump, who presided over the trial, noted that “we cannot pinpoint the person (the attacker) behind them.”

“However, if there was an attempt to abduct a woman who was the mistress of the Maharaja of Indore for a decade, it is not unreasonable to consider Indore as the area from which the attack might have originated,” the bench said. commented.

The importance of the case means the British government must take swift action against the Maharaja. They gave him a choice: either accept a commission of inquiry or abdicate, according to documents submitted to India’s parliament.

The Maharaja chose to withdraw.

He wrote in a letter to the British government: “I relinquish the throne in favor of my son on the condition that there will be no further investigation into my alleged links to the Malabar Hill tragedy.”

After abdicating the throne, the Maharaja caused further controversy by insisting on marrying an American woman against the wishes of his family and community. She eventually converted to Hinduism and they married, according to a British Home Office report.

Meanwhile, Mumtaz Begum received offers from Hollywood and later moved to the United States to try his luck. After that she disappeared.