Mike Wendling/BBC News

Mike Wendling/BBC NewsWith a flurry of snow falling outside, worshipers gathered at Chicago’s Lincoln United Methodist Church to pray for what will happen next week when Donald Trump is inaugurated and for what the president-elect has promised to begin next week, the largest presidential election in U.S. history. Preparing for undocumented immigrant deportations.

“(January) 20th is coming soon,” Pastor Tanya Lozano-Washington told the congregation after handing out steaming cups of Mexican hot chocolate and coffee to the crowd of about 60 people. “

The church is located in Pilsen, a predominantly Latino neighborhood that has long been a hub for pro-immigration activists in the city’s large Hispanic community. But with in-person Spanish-language services canceled, Sunday services are now only available in English.

The decision was made to move the gatherings online amid concerns they could be targeted by anti-immigration activists or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The incoming president says he will deport millions of illegal immigrants and threatens workplace raids, amid reports he may Repeal long-standing policy banning ICE from arresting churches.

“The threat is very real. It is very active,” said one parishioner, American-born David Cruseno.

Cruzeno said his mother entered the country illegally from Mexico but has worked and paid taxes in the United States for 30 years.

“With the new government coming in, it’s almost like a witch hunt,” he told the BBC. “I feel like we are being singled out and targeted in an unfair way, despite our endless collaboration with this country.”

But across the country, more than 1,400 miles (2,253 kilometers) south in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, another largely immigrant community has a very different view of the upcoming inauguration — one that Showing the Latino community’s stance on illegal immigration and Donald Trump’s approach to the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Immigration is critical … but it has to be done in the right way,” said local resident David Porras, a rancher, farmer and botanist.

“But with Trump, we’re going to do the right thing.”

The area is separated from Mexico by only dark, shallow, narrow rivers and dense vegetation and mesquite – and locals say the daily reality of living on the border increasingly exposes them to what many see as illegal immigration. Danger.

“I’ve had (immigrant) family members knocking on my back door asking for water and shelter,” said Starr County resident Amanda Garcia, where nearly 97 percent of Starr County residents identify as Latino , making it the county with the largest Latino population in the United States outside of Puerto Rico.

“We had an incident where a young lady was alone with two men and you could tell she was tired and was being abused.”

Bernd Debsmann Jr/BBC News

Bernd Debsmann Jr/BBC NewsIn dozens of interviews conducted in two counties in the Rio Grande Valley, Starr and neighboring Hidalgo, residents described a range of other border-related incidents, from waking up to find immigrants in their property, to witnessing busts of houses used by cartels for drug stashes, or dangerous high-speed chases between authorities and smugglers.

In predominantly Latino areas of Texas, many are immigrants themselves or are the children and grandchildren of immigrants. Starr County, once a reliably Democratic stronghold in “red” Texas, is swinging in Trump’s favor in the 2024 election — the first time it has gone Republican in more than 130 years Win the county.

Nationally, Trump received about 45% of the Latino vote, a massive 14-point increase from the 2020 election.

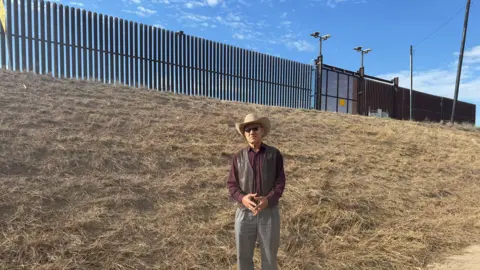

Bernd Debsmann/BBC News

Bernd Debsmann/BBC NewsLocals say the victory in Starr County was due in large part to Trump’s stance on the border.

“We live in a country of order and law,” said Demesio Guerrero, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Mexico who lives in the town of Hidalgo, across the international bridge from the cartel-ridden Mexican city of Reynosa. Looking at each other.

“We have to be able (to tell) who’s coming in and out,” Mr. Guerrero added in Spanish, just meters away from a tall brown metal barrier that represented the end of America. “Otherwise, this country will fail.”

Like other Trump supporters in the Rio Grande Valley, Guerrero has repeatedly said he is “not against immigration.”

“But they should do it the right way,” he said. “Just like everyone else.”

Marisa Garcia, a resident of Rio Grande City in Starr County, said Trump is “not anti-immigrant or racist at all.”

“We’re just tired of them (undocumented immigrants) coming and thinking they can do whatever they want on our property or our land and take advantage of the system,” she added. “It’s not racist to say things need to change and we need to benefit from it.”

Support for deportations is so strong that the Texas government offered Donald Trump 1,400 acres (567 hectares) of land outside Rio Grande City to build detention facilities for undocumented immigrants – Germany The ACLU of Texas described the controversial move as “mass incarceration” that would “encourage civil rights violations.”

While the property, nestled between a quiet farm-to-market road and the Rio Grande River, is currently quiet, town officials believe it could eventually be a boon to the area.

“If you look at it from a development perspective, it’s a good thing for the city’s economy,” Rio Grande City Manager Gilberto Millan told the BBC.

“Obviously, as a detention area, it has some negative connotations,” he said. “You can look at it that way, but obviously you need a place to house these people.”

BerndDebusmann Jr/BBC News

BerndDebusmann Jr/BBC NewsThe number of migrants arriving through Mexico is on a sharp decline, with crossings last month being the lowest since January 2020

But the issue remains very much alive on the streets of cities far from the southern border, such as Chicago.

It is one of several Democratic-run cities that have enacted so-called “sanctuary city” laws that limit local police cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

In response, Republican governors of southern states such as Texas and Florida have sent thousands of migrants north by bus and plane since 2022.

Tom Homan, Trump’s appointee to run border policy, told a Republican gathering in Chicago last month that the Midwestern city would become “ground zero” for mass deportations.

“On January 21, you’re going to have a lot of ICE agents in your city looking for criminals and gang members,” Homan said. “Believe it. It’s going to happen.”

Many local politicians, including Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson and the state’s governor, J.B. Pritzker, continue to support sanctuary city laws, known here as “welcoming city” ordinances.

But the policy was not universally popular. In November, Trump made gains in many Latino communities.

Recently, two Hispanic Democratic lawmakers tried to amend the ordinance and allow some cooperation between Chicago police and federal authorities. Their measures were blocked by Johnson and his progressive allies on Wednesday.

Mike Wendling/BBC News

Mike Wendling/BBC NewsFor now, worshipers at Lincoln United Methodist Church are making plans and watching closely to see how Trump’s plan plays out.

“I’m scared, but I can’t imagine what it feels like to be undocumented,” said D Camacho, a 21-year-old legal immigrant from Mexico who was part of the Sunday church congregation.

Mexican consular officials in Chicago and elsewhere in the United States also said they were developing a mobile app that would allow Mexican migrants to alert relatives and consular officials if they were detained and potentially deported.

Mexican officials described the system as a “panic button.”

Lincoln United organizers have also reached out to legal experts to provide locals with advice on how to look after their finances or arrange childcare in the event of deportation, and to help produce IDs in English containing details of immigrant family members and other information. certificate.

Several second-generation immigrants here said they are working to improve their Spanish so they can deliver legal messages or translate for immigrants interviewed by authorities.

“If someone with five children is taken away, who is going to take the children? Will they go to social services? Will the family be torn apart?” said Pastor Emma Lozano, Tanya Lozano- The Reverend Washington’s mother is also a long-time community activist and church elder.

“These are the questions people are asking,” she said. “‘How can we protect our families — what’s the plan?'”