AFP

AFPThe outlines of a Gaza ceasefire and hostage release deal currently being discussed by Israel and Hamas in indirect talks in Doha have been on the table since May. So why, after being frozen for eight months during the war, were people expecting it to work again?

Several things have changed – both politically and practically.

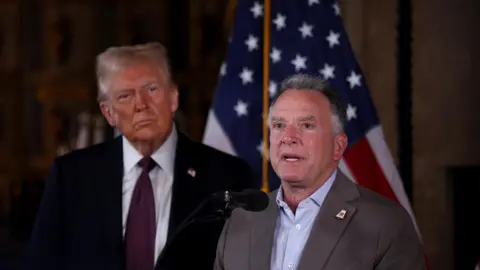

The first is the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the United States.

he has Threats that ‘hell’ will break out If the hostages are not released before he takes office on January 20th.

Hamas is likely to interpret this as a signal that the fragile brakes on the Biden administration’s attempts to rein in Israel’s government will also be lifted, although it is difficult to imagine what that would mean for a territory already devastated by 15 months of war.

Israel is also feeling pressure from the incoming president to end the conflict in Gaza, which could interfere with Trump’s hopes for a broader regional deal and his ideal image as a president who ends the war.

Reuters

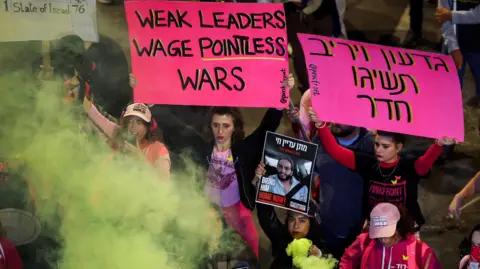

ReutersOn the other hand, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu faces continued pressure from his far-right coalition allies to continue the war.

But Trump could also be an asset in persuading allies to accept a deal and stay in government. The new US president and his appointed Israeli ambassador are seen as supporting Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, as is Israel’s far-right Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich. has said he wants to annex.

But after meeting with the Israeli Prime Minister last night, Smotrich seemed unconvinced, writing on social media that the current agreement was “a disaster” for Israel’s national security and that he would not support it.

Still, some in Israel believe both Smotrich and his far-right ally National Security Minister Itamar Bengvir see their current roles in the Israeli government as their best chance to consolidate control of the West Bank. , especially with Trump returning to the West Bank. White House, they are unlikely to follow through on their threat to withdraw.

Reuters

ReutersThe second change is the increasing pressure on Netanyahu from his own military establishment.

It has been widely reported that key figures have repeatedly challenged him on dwindling military targets to continue the war in the wake of the killing of top Hamas leaders and the destruction of Gaza.

The killing of 10 Israeli soldiers in Gaza last week has refocused attention on the cost of Israel’s war and the long-standing question of whether Netanyahu’s promised “total victory” over Hamas can be achieved .

Some analysts now believe that Hamas is rebuilding faster than Israel can defeat it, and that Israel needs to rethink its strategy.

There is a third – regional – shift that also affects the shift in expectations here: the weakening and erosion of Hamas’ allies. Iran’s “Axis of Resistance”From Hezbollah in Lebanon to Bashar Assad in Syria and the killing of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar in Gaza.

Reuters

ReutersFor all these reasons, now is seen as the best opportunity in months to bridge the differences between Israel and Hamas and end the war.

In the eight months since the last talks, the differences between the two sides have not changed.

Key among them is the direct conflict between Hamas, whose main concern is wanting an end to the war, and Israel, which wants to leave the door open for a resumption of the conflict, whether for political or military reasons.

this deal, As President Joe Biden outlined in MayDivided into three phases, the permanent ceasefire only takes effect in the second phase.

Success now may depend on finding guarantees to allay Hamas’ concerns that Israel will withdraw from the deal after the first phase of releasing the hostages.

It is also unclear at this stage how the territory from which Israel will withdraw its troops will be managed.

But diplomatic networks have crisscrossed the region over the past week, with Netanyahu sending the head of Israel’s security apparatus and a key political adviser to talks in Doha, in encouraging signs.

Palestinian detainee coordinator Qadoura Fares will also travel to Doha.

The deal isn’t done yet – and previous talks have broken down.

The old deal is sparking new hope, in part because the negotiations are taking place in a new regional context, with growing pressure from key allies internally and abroad.