U.S. prosecutors said Wednesday they were discussing a possible plea deal Ismael “El Mayo” Zambadathe long-elusive Mexican drug lord who was arrested last summer and whose son could testify against him if he goes on trial.

Assistant US Attorney Francisco Navarro said plea talks with Zambada, a leader of the powerful Mexican Sinaloa cartelso far they have not borne fruit, but prosecutors want to keep trying. The judge scheduled a hearing for April 22 for an update.

Zambada’s lead attorney, Frank Perez, declined to comment on the hearings.

It’s common for prosecutors and defense attorneys to explore whether they can reach a deal, and talks don’t necessarily lead anywhere.

Zambada was an attentive and active participant during Wednesday’s hearing, which focused on whether he wanted Perez to continue representing him even as he represents a potential government witness in the case – Zambada’s son Vicente Zambada.

– I don’t want another lawyer – said the father through the court interpreter. – I want him, although this could be a conflict if he represents me and my son.

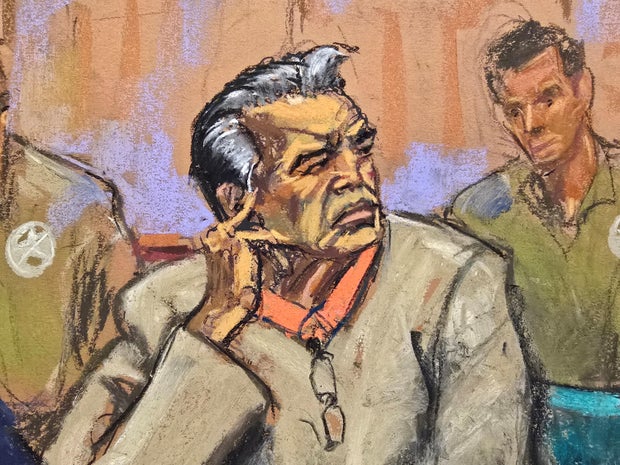

Jane Rosenberg / REUTERS

The younger Zambada was himself indicted and took a plea deal in the long-running and extensive US prosecution of Sinaloa cartel figures. He testified for the government at the trial of the cartel’s infamous and now imprisoned co-founder, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzman.

Working alongside Guzman, Ismael Zambada kept a low profile and was believed to have concentrated more on the smuggling business than extreme brutality, serving as a strategist and negotiator involved in day-to-day operations, authorities said.

At Guzmán’s trial, Vicente Zambada told how his father and Guzmán ran the cartel together. At one point he described corrupt Mexican politicians asking if the union could help them ship 100 tons of cocaine in an oil tanker.

“They wanted to know if my dad and Chapo could provide that amount of cocaine,” he told the jury in the same Brooklyn federal courthouse where his father is on trial. At another point, Vicente Zambada recalled hearing a rival drug gang leader say he wanted to kill Ismael Zambada and Guzman to avenge the botched murder.

Prosecutors said in a court document last month that the son could be called to testify against his father, which could pose a conflict of interest for Perez. For example, he would be prevented from cross-examining his son because of the loyalty he owed to both clients.

Defense attorneys sometimes have potential conflicts of interest with their clients, and federal courts have outlined the steps judges should take in such situations. Among them is for an independent lawyer to advise defendants as they consider what to do about a potential conflict. Zambada had one at Wednesday’s hearing.

Zambada said he realized there might be problems with Perez representing him and his son — “for example, that he would have to hide from me the information he got from Vicente.”

U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan eventually agreed that Perez could stay on the case, noting that Ismael Zambada also had other attorneys who could handle any part involving his son.

The police had been looking for the elder Zambada for years before him a stunning arrest in July at an airport near El Paso, Texas, after arriving on a private jet with one of Guzmán’s sons, Joaquín Guzmán López. He was also wanted by the American authorities.

Zambada said he was kidnapped in Mexico and dragged to the US by Guzmán López, whose lawyer denies these claims. Joaquín Guzmán López and his brother Ovidio are negotiating with the US government to plead guilty, their lawyers said this month in a Chicago courtroom.

After the July arrests and Zambada’s kidnapping charges, terrible fighting broke out in Mexico between a cartel faction loyal to him and another linked to the “Chapitos”, Guzmán’s sons.

The Chapitos used corkscrews, electric shock and hot chili torment their rivals while some of their victims were “fed dead or alive to tigers,” according to the indictment published by the US Department of Justice.

In the past few months, bodies have turned up all over Sinaloa, often left on the streets or in cars hats on the head or pizza slices or boxes attached to them with knives. Pizzas and sombreros have become informal symbols of warring cartel factions, emphasizing the brutality of their warfare.

The chain of events also strained relations between Mexico and the United States.

The first, then Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and the current one President Claudia Sheinbaum he laid some of the blame for the bloodshed at the feet of Washington, saying that American arrests had uncorked the trouble.

The outgoing US ambassador to Mexico, Ken Salazar, responded that it was “incomprehensible” to suggest that the cartel wars were Washington’s fault. He then claimed that the Mexican government had stopped cooperating with Washington in the fight against cartels and was burying its head in the sand about police violence and corruption.

Mexico’s foreign ministry reacted by expressing “surprise” in an official note to the US embassy at the envoy’s statement.