When teenager Axel Rudakubana went on a murderous rampage on the beach in the town of Southport last July, he not only destroyed the lives of his victims and their families but also sent shockwaves through British society.

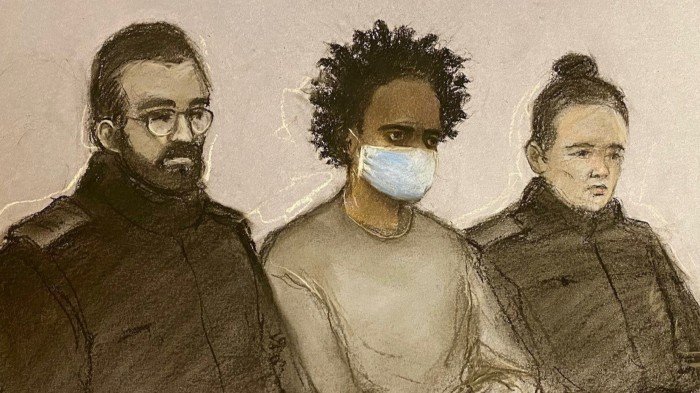

On Thursday the 18 year old received a 52 years in prison for killing three little girls and maiming 10 other people, an atrocity that was followed by a wave of online disinformation and anti-immigration rioting across England.

When the full details of Rudakubana’s harrowing history finally emerged this week, they prompted a fierce debate about the UK’s approach to open justice, as well as the state’s understanding of modern terrorism.

Rudakubana was arrested at the scene of the July killing at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class, standing over the body of a child with a kitchen knife.

In the following days and weeks, police released few details. Disinformation began to spread online, including incorrect claims that the attacker was an illegal immigrant.

Violent race riots followed and the authorities were later accused of a cover-up, especially by those on the right of British politics.

It is a claim that police, prosecutors and Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, himself a senior lawyer and former head of the Crown Prosecution Service, have repeatedly denied.

“If this trial collapses because I or anyone else reveals important details while the police are investigating — while the case is being built, while we’re waiting for a verdict — then the bad guy who committed these crimes could keep a free man away,” Starmer said Tuesday.

Starmer’s position, and that of prosecutors, is based on contempt of court laws in Britain dating back to the early 1980s, which restrict what information can be released before a trial to prevent jurors from transferable.

However, lawyer Jonathan Hall KC, who currently reviews terrorism law for the government, called the state’s interpretation of contempt law in the Southport case “too cautious”.

The police could, he told the Financial Times, safely release Rudakubana’s age, ethnicity, nationality, his birthplace in Cardiff and the fact that he comes from a Rwandan Christian background.

Naming him would be more complicated, since he was 17 at the time, but Hall said prosecutors can and should apply for a court order to do so.

“Imagine if (the police) had put a clear, calm, authoritative, honest, transparent statement on Twitter (now X) earlier,” he said.

“Some people will of course believe the worst, or a conspiracy theory, but most people are just looking for information.”

The state’s silence can be ironically counterproductive at trial, Hall said, because the jury may have disinformation in their minds.

Today’s justice system would do well to “refine” its understanding of what “bias” means in an age of social media, he said, while reviewing decades of contempt of court laws.

The case has also sparked debate about the country’s understanding of, and response to, acts of terrorism.

Within days of the Southport killings, police discovered Rudakubana had an al-Qaeda training manual.

Prosecutors would later argue that it was used to plan the attack. He also made the deadly poison ricin in his bedroom, before hiding it in a plastic box under his bed.

But while he was charged with possession of terror-related material, he was not charged with committing an act of terror. Even the police working on the inquiry say they initially struggled to understand why.

“I say: is this not now terrorism, is this not now terrorism, is this not now terrorism?” recalled senior investigating officer Jason Pye, a detective chief inspector at Merseyside police, of his conversations with prosecutors as the evidence unfolded.

A terrorism charge would also be more straightforward in his investigation, he said. Under terrorism legislation, Rudakubana could be jailed for seven days.

Without it, police have a maximum of 72 hours to put together their case and collect medical evidence related to the 13 victims.

“It absolutely means we have time to do a lot of things,” Pye said of a terrorism charge.

According to prosecutors, the large amount of material found on Rudakubana’s 43 devices — combined with his lack of explanation for his actions in the interview — meant he could not be charged under the Terrorism Act 2000.

That defines terrorism as “for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause”. It was later updated to include racial ideology.

Among the more than 164,000 documents seized were violent material related to the Nazis, Gaza, Grozny and Iraq, as well as footage of attack on Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel in Australia in April.

“He’s not fighting for a cause,” prosecutor Deanna Heer said Thursday. “His purpose was to kill.”

Starmer said this week that he understood “why people wonder what the word ‘terrorism’ means”.

“And so, if the law needs to change to recognize this new and dangerous threat, then we will change it – and quickly,” he added.

However, Hall, who is currently reviewing the legislation for home secretary Yvette Cooper, said she was “skeptical” about expanding the definition of terrorism.

Casting the net wider, he said, could bring in individuals like football hooligans or organized criminals.

Rudakubana’s case has also prompted questions about how well Britain’s anti-extremism agencies are equipped to deal with young people targeted for violence.

In 2022, aged 15, he told Lancashire police that he thought about poisoning people and making poison for that purpose, which he later did. The force said it would not comment ahead of a public inquiry.

Rudakubana was also referred to the government’s Prevent anti-extremism program three times between 2019 and 2021.

He was initially referred at age 13, when his school noticed him researching school shootings online.

He was later flagged for posting on Instagram about former Libyan dictator Colonel Gaddafi, while in April 2021 he was seen looking for the 2017 London Bridge terror attacks at school.

Each time, Prevent closed the case, announcing that there was no coherent ideology behind his actions. He has not been a subject of interest to the counterterror police.

Speaking before the sentencing, Vicki Evans, senior national co-ordinator for counterterrorism policing, said that at the time of her referrals the program was not catching up with the new generation of extremists.

“At the time Prevention was a collaborative response to the increasing prevalence of extreme violence, but it was less developed than it is today,” he said.

“Although advances to help address this challenge have been made,” he added, “questions are rightly being asked about what more needs to be done.”