BBC Eye Survey

British Broadcasting Corporation

British Broadcasting CorporationWhen Zhang Junjie was 17, he decided to protest outside the university against the regulations imposed by the Chinese government. Within days, he was admitted to a mental hospital and treated for schizophrenia.

Junjie is one of dozens of people identified by the BBC as being hospitalized for protesting or complaining to authorities.

Many of the people we interviewed had been treated with antipsychotics and, in some cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) without their consent.

There have been reports for decades that China has used hospitalization as a way to detain dissident citizens without involving the courts. However, the BBC has discovered that one of the issues the legislation seeks to address has recently made a comeback.

Junjie said he was restrained and beaten by hospital staff before being forced to take medication.

His ordeal began in 2022 when he protested against China’s harsh lockdown policies. He said his professors spotted him within five minutes and contacted his father, who took him home. He said his father called the police and the next day, his 18th birthday, two men drove him to what they claimed was a coronavirus testing center but was actually a hospital.

“The doctors told me that I had a serious mental illness… Then they tied me to the bed. The nurses and doctors repeatedly told me that because of my views on the party and the government, I must be mentally ill. It was terrible.” ” he told BBC World Service. He stayed there for 12 days.

Junjie believes his father felt forced to hand him over to the authorities because he worked for local government.

More than a month after being discharged from the hospital, Junjie was arrested again. He defied a ban on fireworks during the Lunar New Year, a measure aimed at combating air pollution, and made a video of himself setting off fireworks. Someone uploaded it online and the police managed to link it to Junjie.

He was accused of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” – a charge often used to silence criticism of the Chinese government. Junjie said that he was forcibly hospitalized for more than two months.

After being discharged from the hospital, Junjie was prescribed antipsychotic medication. We saw aripiprazole prescribed, used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“Taking drugs made me feel like my brain was a mess,” he said, adding that police would come to his home to check if he had taken drugs.

Fearing a third hospitalization, Junjie decided to leave China. He told his parents he was returning to university to pack up his room, but in fact, he fled to New Zealand.

He did not say goodbye to family or friends.

Junjie is one of 59 people identified by the BBC – either by speaking to them or their relatives, or by reviewing court documents – who have been admitted to hospital for mental health reasons after protesting or challenging authorities.

The Chinese government has acknowledged the problem – China’s 2013 Mental Health Law was designed to curb such abuse, making it illegal to treat people without mental illness. It also makes clear that psychiatric admission must be voluntary unless the patient poses a danger to themselves or others.

In fact, a prominent Chinese lawyer told BBC World Service that there has been a recent surge in the number of people being forcibly detained in mental health hospitals. Huang Xuetao, who helped draft the law, blames it on a weakening of civil society and a lack of checks and balances.

“I’ve come across many cases like this. Police want power but avoid responsibility,” he said. “Anyone who knows the shortcomings of the system can abuse it.”

An activist named Xie Lijian told us that in 2018, he received treatment for mental illness without his consent.

Li Jian said he was arrested for participating in a factory protest demanding higher wages. He said police questioned him for three days before sending him to a mental hospital.

Like Junjie, Li Jian said he also took antipsychotic drugs, which impaired his critical thinking.

After a week in the hospital, he said he refused to take any more medication. After an argument with staff and being told he was causing trouble, Li Jian was sent to undergo ECT – a treatment that passes an electric current through the patient’s brain.

“It hurts from head to toe. My whole body feels like it’s not my own. It’s really painful. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. An electric shock. One time, one electric shock, one electric shock, one electric shock, one electric shock Once, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, electric shock, stop, several times, I fainted, I felt like I was being electrocuted. “I was dying,” he said.

He said he was discharged from the hospital after 52 days. He now has a part-time job in Los Angeles and is seeking asylum in the United States.

In 2019, the year after Li Jian said he was hospitalized, the Chinese Medical Doctor Association updated its ECT guidelines to note that the treatment could only be performed under general anesthesia with consent.

We wanted to know more about physician involvement in such cases.

Speaking to foreign media outlets such as the BBC without permission could get them into trouble, so our only option was to go undercover.

We made appointments for telephone consultations with doctors at four hospitals which, according to our evidence, were involved in forced hospitalization.

We created a story about a relative who was hospitalized for posting anti-government comments online, and asked five doctors if they had ever encountered a case where police had sent a patient to hospital.

Four confirmed they had.

“Psychiatry has something called ‘troublemaker’ admissions,” one doctor told us.

Another doctor at the hospital where Junjie was being held appeared to confirm his account that police continued to monitor the patient after he was discharged.

“Police will check on you at home to make sure you take your medication. If you don’t take your medication you could be breaking the law again,” they said.

We contacted the hospitals involved for comment but did not receive a response.

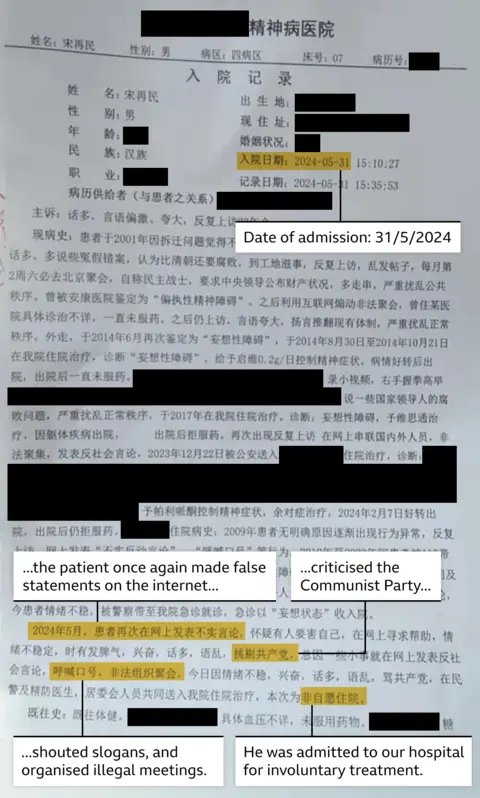

Our access to the medical records of pro-democracy activist Song Zaimin, who was hospitalized for the fifth time last year, clearly illustrates how closely political views appear to be tied to psychiatric diagnoses.

“Today he… talked a lot, was incoherent, and criticized the Communist Party. So, he was sent to our hospital for hospitalization by the police, doctors and the local neighborhood committee. This was involuntary hospitalization,” it said.

We asked Professor Thomas G Schulze, President-elect of the World Psychiatric Association, to review these notes. He replied:

“No one should be involuntarily admitted and treated against their will in the circumstances described here. This reeks of political abuse.”

According to a group of Chinese citizen journalists who have documented abuses of the Mental Health Law, more than 200 people reported that they were wrongly hospitalized by authorities between 2013 and 2017.

Their coverage ended in 2017 when the group’s founder was arrested and subsequently jailed.

For victims seeking justice, the legal system seems stacked against them.

A man we will call Mr. Li was hospitalized in 2023 for protesting against local police, and he attempted to take legal action against authorities for imprisoning him.

Unlike Junjie, doctors told Mr Li he was not sick, but police later arranged for an outside psychiatrist to evaluate him, who diagnosed him with bipolar disorder and he was detained for 45 days.

After his release, he decided to question the diagnosis.

“If I don’t sue the police, it will be as if I admit that I have a mental illness. It will have a significant impact on my future and my freedom because the police can use this as a reason to lock me up at any time,” he said.

In China, the records of anyone diagnosed with severe mental illness can be shared with police and even local residents’ committees.

But Mr Li was unsuccessful – the court dismissed his appeal.

“We hear our leaders talk about the rule of law,” he told us. “We never dreamed that one day we would end up in a mental hospital.”

The BBC found that 112 people listed on the official website of Chinese court verdicts attempted to take legal action against police, local authorities or hospitals between 2013 and 2024 over such treatments.

About 40% of these plaintiffs had been involved in complaints against the authorities. Only two won their cases.

The site appears to have been censored – five other cases we investigated were missing from the database.

Nicola McBean, of London-based human rights group Rights Practice, said the problem was that police enjoyed “considerable discretion” in dealing with “troublemakers”.

“Bypassing the process of sending someone to a psychiatric hospital is both too easy and too useful a tool for local authorities.”

Chinese social media

Chinese social mediaAttention is now focused on the fate of vlogger Li Yixue who accused a police officer of sexual assault. Yixue is said to have recently been hospitalized for a second time after a social media post discussing the experience went viral. She is reportedly currently under surveillance at a hotel.

We have submitted our findings to the Chinese Embassy in the UK. Last year, the Chinese Communist Party “reaffirmed” the need to “improve legal mechanisms” and “clearly prohibit illegal detention and other methods of illegally depriving or restricting citizens’ personal freedoms.”

Additional reporting by Georgina Lam and Betty Knight