British Broadcasting Corporation

British Broadcasting CorporationWhen Pte Oleksander Bezverkhny was evacuated to Kiev’s Feofaniya Hospital, few believed he would survive. The 27-year-old man suffered serious abdominal injuries and shrapnel tore his hip. Both of his legs were amputated.

Then doctors discovered that his infection had become resistant to commonly used antibiotics, and the already daunting task of saving his life became almost hopeless.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is when bacteria evolve and learn how to defend themselves against antibiotics and other drugs, rendering them ineffective.

Ukraine is not the only country affected by this problem: around 1.4 million people died from AMR infections globally in 2021, and there were 66,730 severe antibiotic-resistant infections in the UK in 2023. However, war appears to have accelerated the spread of bacterial resistance. Multidrug-resistant pathogens in Ukraine.

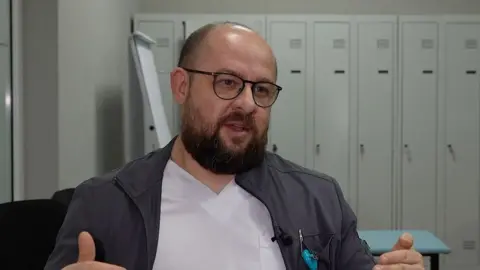

Clinics treating war-wounded people have seen a sharp increase in cases of antimicrobial resistance. Dr. Andriy Strokan, deputy chief physician, said that more than 80 percent of all patients admitted to Feofaniya Hospital have infections caused by microorganisms that are resistant to antibiotics.

Ironically, antimicrobial-resistant infections often originate in healthcare facilities.

Medical personnel try to follow strict hygiene protocols and use protective equipment to minimize the spread of these infections, but facilities can be overwhelmed by war-wounded personnel.

Dr. Volodymyr Dubyna, director of the Mechnikov Hospital ICU, said his hospital had increased the number of beds from 16 to 50 since the beginning of the Russian invasion. At the same time, staffing levels declined as many employees fled the war or joined the military themselves.

These conditions can influence the spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, Dr. Strokan explained. “In the surgical unit, one nurse is responsible for 15 to 20 patients,” he said. “She was physically unable to scrub her hands as much and as frequently as required to avoid spreading infection.”

The nature of the war also means patients are exposed to many more strains of infection than in peacetime. When soldiers are evacuated for medical reasons, they often pass through multiple facilities, each harboring their own strains of antimicrobial resistance. While medical professionals say this is unavoidable due to the scale of the war, it will only exacerbate the spread of antimicrobial-resistant infections.

This was the case for Pte Bezverkhny, who received treatment at three different institutions before arriving at a Kiev hospital. Because his infection couldn’t be treated with conventional medications, his condition worsened and he developed sepsis five times.

The situation differs from other recent conflicts, such as the war in Afghanistan, where Western soldiers would be stabilized on site and then flown to European clinics, rather than passing through multiple different local facilities.

Dr. Dubina said this was not possible in Ukraine because there had not been an influx of patients since World War II. The Dnipro hospital where he was located was adjacent to the frontline area. Once his patients are stable enough, they are moved to another clinic — if there is space — to free up capacity.

“In terms of microbial control, that means they spread (the bacteria) further. But if we don’t do that, we can’t work. That’s a disaster.”

Due to the high number of casualties, Ukrainian hospitals are often unable to isolate infected patients, meaning multi-drug-resistant and dangerous bacteria spread unchecked.

The problem is that the infections they cause must be treated with special antibiotics from a “stockpile” list. But the more drugs doctors prescribe, the faster the bacteria adapt, rendering these antibiotics ineffective.

“We have to balance our scales,” Dr. Strokan explains. “On the one hand, we have to save patients. On the other hand, we cannot breed new microbes with antimicrobial resistance.”

In the case of Pte Bezverkhny, doctors had to use very expensive antibiotics, which volunteers procured from abroad. After a year of hospitalization and more than 100 surgeries, his condition is no longer life-threatening.

Doctors managed to save his life. But as pathogens become more resistant, the fight to save others will only become more difficult.