Caroline Bazzi/Jinha Agency

Caroline Bazzi/Jinha AgencyLast fall, as the war in Lebanon raged, Hania Zataari, a mechanical engineer working for Lebanon’s Ministry of Industry, put her skills to use. Originally from Sidon in southern Lebanon, she created a chatbot on WhatsApp to simplify the process of receiving much-needed aid.

“They lost their houses, their savings, their jobs, everything they built,” Haniya said, referring to those forced from their homes by the war.

On September 23, Israel significantly escalated its offensive against the Lebanese armed organization Hezbollah. Since Hezbollah attacked Israel in October 2023, Israel has been in an escalating conflict with Hezbollah.

According to the Lebanese government, it was one of Lebanon’s deadliest conflicts in nearly 20 years, killing at least 492 people.

Thousands of families fled to Sidon after the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) attacked an alleged 1,600 Hezbollah positions in Lebanon.

Many displaced people have sought shelter in schools and other public buildings, but many who fled their homes have been forced to rent elsewhere or live with family members, Haniyeh said.

It is these people who do not receive direct government support that she wants to help. Hania used her programming skills to create “aid bots” to bridge the gap between aid supply and demand.

The assistive bot is a chatbot – an artificial intelligence system designed to communicate with users online – linked to WhatsApp. It’s programmed to ask simple questions about the type of assistance people need, as well as their name and location.

The information is then logged into a Google spreadsheet that Hania and her team of unpaid volunteers made up of friends and family can use to distribute aid such as food, blankets, mattresses, medicine and clothing.

Hania built the bot in her spare time using the website Callbell.eu, which is commonly used by businesses to interact with customers on Meta’s platforms, such as WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook Messenger.

She explained that the bot, which is still in use today, allows aid to be distributed more efficiently as it reduces the time it takes her to respond to requests for aid via WhatsApp.

“I’m not interested in knowing their names. I just need to know where they are so I can manage the delivery,” she said.

Take, for example, a request for infant formula. Hania said the robot asks for the age of the baby and the quantity required so that she and her team can provide it.

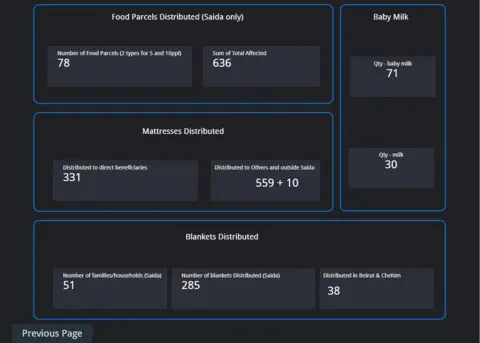

The project is funded by donations from Lebanese living abroad, she said. She created a public dashboard to record how much money was spent on the project and how much aid she and her team distributed.

As of this writing, they have delivered 78 food parcels, 900 mattresses and 323 blankets to families of 5 to 10 people in Sidon and other areas of Lebanon.

Last October, 47-year-old Kaldon Abbas and his family received a call from the Israel Defense Forces urging them to leave their home in Najariyah for their own safety.

Seventeen people, ranging in age from nine to 78, sleep under one roof in a rented three-bed flat in Seaton.

Carlton said he, his wife and children, and his brother’s family all slept on mattresses they requested using an assistive robot in the apartment’s hallway. They also asked for blankets, food and cleaning agents.

Unlike his neighbors, he was unable to return home. It was destroyed 11 days later in an attack confirmed by Israel. The Israel Defense Forces told the BBC it “attacked terror infrastructure”.

When we raised this allegation with Khaldun, he denied any links to Hezbollah or any other political party.

“This is not the first time that Sidon has opened its doors to displaced people,” Haniya explained, referring to the influx of people arriving into the city.

Sidon has a reputation for hosting internally displaced people from the Lebanese-Israeli border region who have been forced to flee their homes.

The most recent conflict began in October 2023, when the war between Israel and Hamas spilled into Lebanon, when Hamas’s ally Hezbollah fired rockets at Israel in support of Gaza.

According to the Lebanese Health Ministry, nearly 4,000 people have died and more than one million people have been displaced. The Defense Ministry did not say how many of them were civilians or combatants.

In Israel, some 60,000 people have been evacuated from northern Israel, and authorities said more than 80 soldiers and 47 civilians were killed.

In November last year, Israel and Lebanon reached a ceasefire agreement. Despite some minor skirmishes, it was largely maintained. But local people say the delivery of aid has not improved.

International NGO Islamic Relief told the BBC that “ongoing displacement in Lebanon is exacerbated by conflict, destruction and evacuation orders, making it difficult to assess and meet the needs of the population in an evolving situation.”

But it’s not just war that’s hampering aid distribution.

Bilal Meri, a volunteer working with Haniya, said many of the problems they faced were caused by “high demand and short supply” of aid.

He attributed this to the severe economic turmoil that has gripped the country since 2019, meaning the Lebanese government has had to rely heavily on funding from creditors and aid groups to purchase goods.

But even NGOs are feeling the pinch. UNICEF Lebanon said it had provided only 20 per cent of the funding they needed and “still faces a significant funding gap”, meaning the charity was unable to support families when they needed it most.

In a country plagued by financial crisis and war, can this aid robot make a real difference?

This is the first time John Bryant, a researcher at the Overseas Development Institute think tank, has heard of chatbots being used in this way in the humanitarian sector.

He said the cultural context in which it was used was commendable. That is, understanding “the channels people use to talk to each other and meet them in their own language.”

However, he’s unsure about its scalability because what works in Lebanon is difficult to replicate elsewhere in the world.

“Technology provides a standard cookie-cutter approach a lot of the time.

“It’s local designers, local translators, trusted human interlocutors, and elements within the system that elevate digital tools into something useful,” he said.

The aid robot may not solve all of Lebanon’s problems, but for the families who use it, it makes life easier.

Additional reporting by Ahmed Abdullah